LENDÜLETBENBioFiz&Biotech&Kutatás

Hőjelenségek

http://tudasbazis.sulinet.hu/hu/termeszettudomanyok/fizika/fizika-7-evfolyam/hojelensegek

Teszt-feladatsorok:

Hőtágulás Hővezetés

Hőáramlás gázokban

Fagyás és olvadás Forrás és lecs apódás

A párolgás ( Hőjelenségek )

+ Kölcsönhatás az anyag részecskéi között

+++ Hőtan +++

| Hőtágulás: | |

| Szilárd testek térfogati hőtágulása | |

| A hőterjedés formái: | |

| Hőáramlás gázokban | |

| Hőáramlás folyadékokban | |

| A fémek hővezetése | |

| A víz rossz hővezető | |

| Halmazállapot-változások: | |

| A forráspont nyomásfüggése | |

| A párolgáshoz energia szükséges | |

| Párolgástól működő hőerőgép | |

| Az olvadáspont nyomásfüggése | |

| Kinetikus gázelmélet: | |

| Különböző halmazállapotok modellezése | |

A kémia/kémikusok pedig:

http://www.sulinet.hu/tlabor/kemia/szoveg/index.htm

"A halmazállapot-változások mindig energiaváltozással járnak.

Energiafelvétellel jár, azaz endoterm folyamat az olvadás, forrás, párolgás és a szublimáció.

Energia leadásával jár, azaz exoterm folyamat a fagyás, a lecsapódás (kondenzáció) és a kristályosodás."

Endoterm változások: a folyamat során a rendszer hőt vesz fel környezetétől, belső energiája nő.

Exoterm változás: a folyamat során hő szabadul fel és adódik át a környezetnek, a rendszer energiája eközben csökken.

/ Exoterm oldódás: a rendszer oldódás során energiát veszít (kötéseinek átrendeződése során azok összenergiája csökken). Ez az energia először saját, illetve közvetlen környezete hőmérsékletét emeli, majd - kisugározva a környezetbe - ismét felveszi a környezet hőmérsékletét. /

Fizika:

Fagyás: a cseppfolyós halmazállapotból a szilárd halmazállapotba való átmenet. Energia felszabadulással járó folyamat.

Lecsapódás: a légnemű halmazállapotból a cseppfolyós halmazállapotba való átmenet. Energia felszabadulással járó folyamat.

Párolgás: a cseppfolyós halmazállapotból a légnemű halmazállapotba való átmenet, amely bármely hőmérsékleten végbemegy. Elvileg minden anyag párolog.

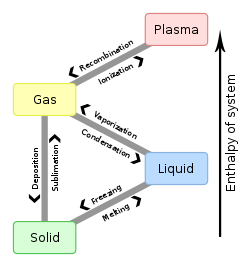

Fázisátalakulás

A fázisátalakulás a természetben gyakran lejátszódó folyamat. Jellemző vonása az, hogy a kiindulásnak tekintett anyagnak számos fizikai tulajdonsága megváltozik a fázisátalakulás során. Számos fázisátalakulást használnak föl a mérnöki gyakorlatban a különféle gépi folyamatokban. A legismertebb fázisátalakulás a víz fagyása, vagy a jég olvadása, a víz elpárolgása, vagy a gőz lecsapódása.

A fizikában

A termodinamika területén a fázisátalakulás egy termodinamikai rendszer átalakulása egyik fázisból a másikba. A fázisátalakulás alatt a rendszer fizikai tulajdonságai hirtelen megváltozhatnak. Például a két fázis térfogata jelentősen eltérhet egymástól (ilyen következik be a víz megfagyásakor, amikor a víz térfogata megnő a jég állapotba alakulva).

A fázisátalakulás kifejezést leggyakrabban a szilárd, a folyadék és a gáz állapot, átalakulásainál használjuk, ritkábban a plazma állapot esetében.

Fázisátalakulások típusai

- Fázisátalakulás egyetlen anyagkomponensnek a szilárd, a folyadék és a gáz fázisai között a hőmérséklet és/vagy a nyomás változásának a hatására:

- Az eutektikus átalakulás, melyben egy két komponensű egyetlen, folyadék fázis hűl le és alakul át két szilárd fázissá. Ugyanez végbemehet szilárd kezdőfázis esetén is. Ezt eutektoid transzformációnak nevezik.

- A peritektikus fázisátalakulás, melyben egy két komponensű egyetlen fázisú szilárd anyag, fölmelegítés hatására átalakul egy szilárd és egy folyadék fázissá.

- A spinodiális dekompozíció, melyben egyetlen fázisú anyagot hűtenek le, amely a lehűlés során szétválik ugyanennek az anyagnak két, különböző összetételű fázisává.

- A ferromágneses és a paramágneses fázisok közötti átalakulás a mágneses anyagokban, a Curie-hőmérsékleten.

- A martenzites átalakulás, amely az acélok edzésekor következik be.

- Változások a kristálytani szerkezetben, például a vas ferrites és az ausztenites szerkezete között.

- A rendezett- rendezetlen szerkezet átalakulása, mint például az alfa-titán-alumínium vémötvözetek esetén.

- A szupravezetés kialakulása bizonyos fémekben, a kritikus hőmérséklet alá hűtéskor.

- Átalaklulás az ásványok allotróp módosulatai között. Például egy anyag amorf és kristályszerkezetü változata között.

Ide sorolható még az a szimmetriasértő átalakulás is, ami az anyagfejlődés-történet korai szakaszában játszódott le.

4. Halmazállapot-változások / Fizika 10.

https://www.mozaweb.hu/Lecke-Fizika-Fizika_10-4_Halmazallapot_valtozasok-99717

4.1. A halmazállapot-változások energetikai vizsgálata

|

Emlékeztető

A környezetünkben található kémiai anyagok háromféle: szilárd, cseppfolyós (vagy folyékony) és légnemű halmazállapotban fordulnak elő.

Az anyagok halmazállapota termikus kölcsönhatások hatására megváltozhat. Az anyagok ilyen – belső szerkezeti változással is együtt járó – állapotváltozását halmazállapot-változásnak nevezzük.

A legegyszerűbb kémiai anyagok, az elemek mindhárom halmazállapotban előfordulhatnak.

|

|

Ha egyszerre együtt van jelen valamely anyag többféle halmazállapotban is, akkor a halmazállapotokat szokás fázisoknak nevezni. Így olvadáskor együtt van az anyag szilárd és folyékony fázisa, párolgáskor és forráskor pedig a folyékony és a gőz fázis. Ennek megfelelően a halmazállapot-változásokat fázisátalakulásoknak is hívjuk. Tágabb értelemben a fázisok a szilárd anyagok különböző kristálymódosulatait is jelenthetik. Így a grafit és a gyémánt a szénnek két különböző szilárd fázisa vagy kristályos módosulata.

|

|

A halmazállapot-változások az energiacsere iránya szerint két csoportba sorolhatók:

|

|

Az ábra szerinti kísérleti elrendezéssel vizsgáljuk meg a szalol (vagy fixírsó) olvadásának folyamatát. Az anyagok várható olvadáspontja 40 C o körüli érték. Egyenletes melegítés során egyenlő időközönként mérjük a kristályos anyag hőmérsékletét. Készítsünk hőmérséklet–idő grafikont! Vegyük fel a grafikont a megolvadt anyag hűtésekor is! Időben egyenletes hőátadást feltételezve arra következtethetünk, hogy a kristályos anyag Δ T hőmérséklet-változása hogyan függ a Δ E b belső energiájának megváltozásától.

|

|

Különböző mennyiségű és minőségű anyagokat olvasztva (vagy fagyasztva) a hőmérséklet–idő grafikonok alapján az alábbi törvényszerűségeket állapíthatjuk meg a testek olvadására és fagyására.

A halmazállapot-változásokhoz az anyagi minőségtől és a külső nyomástól függő meghatározott hőmérsékleti pontok tartoznak.

Olvadáspont(fagyáspont): az a hőmérsékleti pont, amelyen az olvadás és a fagyás folyamata végbemegy.

A kétfázisú rendszer hőmérséklete mindaddig állandó marad, amíg az olvadás vagy fagyás folyamata tart.

Az olvadáspont függ az anyagi minőségtől és a külső nyomástól.

Az olvadáskor a rendszer által felvett vagy a fagyáskor leadott Q hőmennyiség egyenesen arányos a megolvadt vagy a megfagyott anyag m tömegével. Az arányossági szorzó az anyagi minőségre jellemző állandó érték, amelyet az anyag olvadáshőjének vagy fagyáshőjének nevezünk.

|

|

Az olvadáshő (fagyáshő) megmutatja, hogy az 1 kg tömegű anyag megolvadásakor (fagyásakor) mekkora a hőcsere az anyag és a környezete között.

Jele: L o , mértékegysége: 1 J k g Az m tömegű test megolvadásakor (megfagyásakor) a felvett (leadott) hőmennyiséget a

Q=L0⋅m

összefüggésből számíthatjuk ki.

|

|

Megfigyelhetjük, hogy nemcsak a forró kávé, a meleg leves vagy a langyos tea párolog, hanem hűvös reggeleken a tó vagy a folyó felszíne is gőzölög. Ekkor a víz hőmérséklete 15–20 C o lehet. Télen a szabadba kiterített vizes, sőt még a fagyott ruha is előbb-utóbb megszárad. Ebből arra következtethetünk, hogy még a fagyáspont körüli hideg víz és a szilárd halmazállapotú jég is képes elpárologni.

|

|

Tapasztalatainkból megállapíthatjuk, hogy a folyadékok felszínéről kiinduló párolgás minden hőmérsékleten végbemegy, a párolgásnak nincs állandó hőmérsékleti pontja. Egyes anyagok jobban, mások kevésbé párolognak.

A kályha mellett gyorsabban szárad meg a vizes ruha, mint a hideg szobában. – Ugyanannyi idő alatt ugyanakkora folyadékfelszínről, azonos külső körülmények között magasabb hőmérsékleten nagyobb tömegű folyadék párolog el. A párolgás gyorsasága növelhető a folyadékfelszín felületének növelésével vagy a felszín feletti páratartalom csökkentésével is.

Kánikulában, strandoláskor gyakran fázunk, amikor a langyos fürdővízből kijövünk, mivel a bőrünk felszínén maradt vízréteg elpárolog, és ekkor hőt von el testünktől. Ugyanezen az elven „működik” a szervezetünk, amikor a túlmelegedés ellen izzadással védekezik. A sportolók fájdalmas sérüléseinek gyors orvoslására gyakran használnak olyan gyorsan párolgó folyadékot, mely intenzív párolgás közben hűti a sérült testrészt, ezzel enyhítve a fájdalmat.

A folyékony anyagok párolgáskor hőt vesznek fel a környezetüktől. A felvett Q hőmennyiség egyenesen arányos az elpárolgott folyadék m tömegével, az arányossági szorzó az anyagra jellemző L p párolgáshő.

|

|

A párolgáshő megadja, hogy mekkora hőmennyiségre van szükség ahhoz, hogy az 1 kg tömegű folyadékból ugyanakkora tömegű és hőmérsékletű gőz legyen.

Az m tömegű folyadék elpárolgásához felvett hőmennyiséget a Q=Lp⋅m

összefüggéssel számíthatjuk ki.

|

|

Egy adott hőmérsékleten történő lecsapódásakor a gőz által a környezetének leadott hőmennyiség megegyezik a párolgás során felvett hőmennyiséggel ( Q le = Q fel ).

Ha a párologás a folyadék belsejében is megindul, akkor a jelenséget forrásnak nevezzük.

|

|

Forráskor a folyadék belsejében lévő levegő- vagy más gázbuborékok a folyadék gőzével telítődnek, térfogatuk megnő, ezért a felszínre emelkednek, ahol belőlük a gőz eltávozik.

|

|

A forrás egy adott hőmérsékleti ponton, a forrásponton* indul meg. A folyadék hőmérséklete forrás közben állandó marad.

|

|

A forráspont értéke függ:

|

|

Ezért használunk zárt edényeket – kukta-fazék, sterilizáló edények – a víz forráspontjának növelésére. Magasabb hőmérsékleten a nyers ételek hamarabb megfőnek, a kórokozók elpusztulnak.

A turisták gyakran tapasztalják, hogy a magas hegységekben, ahol a légnyomás értéke kisebb, a víz már 100 C o alatti hőmérsékleten elkezd forrni. Ez a főzéskor gondot okoz. Ilyen nyomáscsökkentést magunk is megvalósíthatunk az ábra jobb oldalán látható kísérlettel, ahol a zárt lombikban felmelegített víz feletti levegő-gőz keverék nyomását vízhűtéssel csökkentjük.

|

|

Mindennapi tapasztalat, hogy nagyobb menynyiségű víz felforralásához több időre, és így több hő felvételére van szükség.

Ha azonos tömegű alkoholt és vizet forralunk azonos körülmények között, akkor az alkohol harmadannyi idő alatt forr el, mint a víz.

Mérésekkel igazolhatjuk, hogy forráskor a folyadék által felvett Q hőmennyiség egyenesen arányos a forrásponton elforralt folyadék m tömegével, és függ az anyagi minőségtől.

|

|

Az m tömegű folyadék elforralásához szükséges hőmennyiség értékét a

Q=Lf⋅m

összefüggésből számíthatjuk ki, ahol L f az anyagra jellemző állandó, az anyag forráshője.

A forráshő megadja, hogy mekkora hőmennyiséget vesz fel a forrásban lévő 1 kg tömegó folyadék ahhoz, hogy a a forrásponttal megegyező hőmérsékletó gőz keletkezzen. |

|

A forráshő kismértékben függ a forrásponttól is, és megegyezik a forrásponthoz tartozó párolgáshővel.

Néhány anyag forráspontja és forráshője 10 5 Pa nyomáson:

|

Amikor a gőz a forrásponton lecsapódik, akkor a forrásakor a környezetétől felvett hőmeny-nyiséget a környezetének visszaadja ( Q le = Q fel ). Ezt használják fel a távfűtő rendszerekben, ahol a hőközpontokban előállított gőzt vezetik jól szigetelt csővezetékeken keresztül a lakásokhoz. Itt a gőz lecsapódásakor jelentős mennyiségű hő szabadul fel.

A termodinamika (ma már ritkán használt magyar nevén hőtan) a fizika energiaátalakulásokkal foglalkozó tudományterülete.

Egy magára hagyott termodinamikai rendszerben az intenzív állapotjelzők eloszlása homogénné válik, vagyis a rendszer egyensúlyi állapotba kerül. Az egyensúlyi állapottal a termosztatika foglalkozik. Minden pontjában ugyanakkora nyomás, hőmérséklet stb. lesz. Termodinamikai elveken (is) alapszik pl.: időjárás-előrejelzés, robbanómotorok, repülőgép-hajtóművek, hűtőszekrény, kuktafazék, kémény. Néhány fogalom, mely kapcsolódik a termodinamikához: tömeg, tömegáram, hőátadás, munka, hő, belső energia, nyomás, fázis, entrópia, entalpia, fajhő, ideális gáz, Carnot-körfolyamat.

Klasszikus termodinamika

0. főtétel: a termodinamikai rendszer egyensúlya

A nulladik főtétel tulajdonképpen nem egyetlen "törvényt", hanem több posztulátumot jelent, amelyek a termodinamikai rendszer egyensúlyával kapcsolatosak. Ezek:

- bármely magára hagyott termodinamikai rendszer egy idő után egyensúlyi állapotba kerül amelyből önmagától nem mozdulhat ki;

- egy egyensúlyban levő termodinamikai rendszer szabadságfokainak száma a környezetével megvalósítható kölcsönhatások számával egyenlő;

- a két testből álló magára hagyott termodinamikai rendszer egyensúlyban van, ha a testek között fellépő kölcsönhatásokat jellemző intenzív állapothatározóik egyenlők;

- az egyensúly tranzitív (ha A rendszer termodinamikai egyensúlyban van C rendszerrel és B rendszer is termodinamikai egyensúlyban van C rendszerrel, akkor ebből következik, hogy A és B rendszer is termodinamikai egyensúlyban van egymással).

I. főtétel – Energiamegmaradás törvénye

A termodinamika első főtétele mennyiségi összefüggést állapít meg a mechanikai munka, a cserélt hő és a belső energia változása között. Egy nyugvó és zárt termodinamikai rendszer belső energiáját, amennyiben annak belsejében nem zajlik le fázisátalakulás vagy kémiai reakció, kétféleképpen lehet megváltoztatni: munkavégzéssel és hőközléssel. A rendszer belső energiájának megváltozása ΔU tehát a vele közölt Q hőmennyiség és a rajta végzett W (bármilyen) munka összege:

Áramló közegre a hő és a technikai munka összege így számolható:

ahol q a hő, wt12 a technikai munka, h az entalpia, c a közegáramlás sebessége, g a gravitációs állandó és z a vizsgált pont magassága (helyzete). Differenciális alakban:

Következménye: Nincs olyan periodikusan működő gép, ú.n. elsőfajú perpetuum mobile (örökmozgó), mely hőfelvétel nélkül képes lenne munkát végezni.

II. főtétel

A második főtétel a spontán folyamatok irányát szabja meg. Több, látszólag lényegesen különböző megfogalmazása van.

- Clausius-féle megfogalmazás (1850.): A természetben nincs olyan folyamat, amelyben a hő önként, külső munkavégzés nélkül hidegebb testről melegebbre menne át. Csakis fordított irányú folyamatok lehetségesek.

- Kelvin-Planck-féle megfogalmazás (1851., 1903.): A természetben nincs olyan folyamat, amelynek során egy test hőt veszít, és ez a hő munkává alakulna át. Szemléletesen egy hajó lehetne ilyen, amelyik a tenger vizéből hőenergiát von el és a kivont hőenergiával hajtja magát. Ez nem mond ellent az energiamegmaradásnak, mégsem kivitelezhető.

Az ilyen gépet másodfajú perpetuum mobile|perpetuum mobilének nevezzük, tehát az állítás szerint nem létezik másodfajú perpetuum-mobile.

A két megfogalmazás egymásból következik, de a levezetése nem teljesen egyszerű.

A második alaptörvénynek ezek és az ezekhez hasonló megfogalmazásai zavarbaejtőek, hiszen a fizika többi, összefüggéseket megállapító törvényeivel szemben valaminek a létezését tagadják. Egy jobb megfogalmazás végett egy új fogalom került bevezetésre: az entrópia. A termodinamika második alaptörvénye az entrópia felhasználásával a következőképpen fogalmazható meg: a spontán folyamatok esetében a magukra hagyott rendszerek entrópiája nem csökkenhet.

III. főtétel

Nernst megfogalmazása szerint az abszolút tiszta kristályos anyagok entrópiája nulla kelvin hőmérsékleten zérus.

Statisztikus termodinamika

0. főtétel

Az egyszerű rendszereknek vannak olyan speciális, u.n. egyensúlyi állapotai, melyek makroszkopikus szempontból egyértelműen jellemezhetőek belső energiájukkal, térfogatukkal, és molekulaszámukkal.

1. főtétel (ekvivalencia tétel)

Egy folyamat során a rendszernek átadott hőt egyértelműen meghatározza a belső energia növekedése és a rendszeren végzett munka az alábbiak szerint:

2. főtétel

Minden egyensúlyi rendszerhez rendelhető egy S függvény, a rendszer entrópiája, mely a rendszer állapotát jellemző extenzív paraméterek függvénye. Az entrópia tulajdonságai:

- A belső energia növekedésével monoton nő

- Extenzív mennyiség

- Részleges egyensúlyi állapot entrópiája megegyezik annak az osztott rendszernek az entrópiájával, amelyből a falak szigetelő tulajdonságainak megszüntetésével keletkezett.

- Az entrópia legyen a lehető legnagyobb érték, amely a falak még megmaradó szigetelő tulajdonságaival összefér.

3. főtétel (Nernst-tétel)

Két olyan állapot entrópiájának a különbsége, amelyek kvázisztatikusan átalakíthatók egymásba,  -nál nullához tart, azaz

-nál nullához tart, azaz

Források

- Litz József: Hőtan

- Hraskó Péter: Termodinamika és statisztikus fizika

Phase transition

|

|

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (May 2014) |

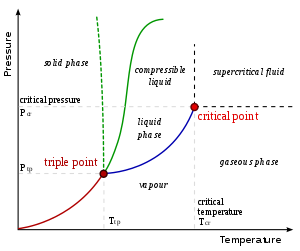

A phase transition is the transformation of a thermodynamic system from one phase or state of matter to another one by heat transfer. The term is most commonly used to describe transitions between solid, liquid and gaseous states of matter, and, in rare cases, plasma. A phase of a thermodynamic system and the states of matter have uniform physical properties, because of their different mass[clarification needed]. During a phase transition of a given medium certain properties of the medium change, often discontinuously, as a result of some external condition, such as temperature, pressure, and others. For example, a liquid may become gas upon heating to the boiling point, resulting in an abrupt change in volume. The measurement of the external conditions at which the transformation occurs is termed the phase transition. Phase transitions are common in nature and used today in many technologies.

Contents

Types of phase transition

Examples of phase transitions include:

- The transitions between the solid, liquid, and gaseous phases of a single component, due to the effects of temperature and/or pressure:

| To | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Liquid | Gas | Plasma | ||

| From | Solid | Solid-solid transformation | Melting | Sublimation | — |

| Liquid | Freezing | — | Boiling / evaporation | — | |

| Gas | Deposition | Condensation | — | Ionization | |

| Plasma | — | — | Recombination / deionization | — | |

-

- (see also vapor pressure and phase diagram)

- A eutectic transformation, in which a two component single phase liquid is cooled and transforms into two solid phases. The same process, but beginning with a solid instead of a liquid is called a eutectoid transformation.

- A peritectic transformation, in which a two component single phase solid is heated and transforms into a solid phase and a liquid phase.

- A spinodal decomposition, in which a single phase is cooled and separates into two different compositions of that same phase.

- Transition to a mesophase between solid and liquid, such as one of the "liquid crystal" phases.

- The transition between the ferromagnetic and paramagnetic phases of magnetic materials at the Curie point.

- The transition between differently ordered, commensurate or incommensurate, magnetic structures, such as in cerium antimonide.

- The martensitic transformation which occurs as one of the many phase transformations in carbon steel and stands as a model for displacive phase transformations.

- Changes in the crystallographic structure such as between ferrite and austenite of iron.

- Order-disorder transitions such as in alpha-titanium aluminides.

- The dependence of the adsorption geometry on coverage and temperature, such as for hydrogen on iron (110).

- The emergence of superconductivity in certain metals and ceramics when cooled below a critical temperature.

- The transition between different molecular structures (polymorphs, allotropes or polyamorphs), especially of solids, such as between an amorphous structure and a crystal structure, between two different crystal structures, or between two amorphous structures.

- Quantum condensation of bosonic fluids (Bose–Einstein condensation). The superfluid transition in liquid helium is an example of this.

- The breaking of symmetries in the laws of physics during the early history of the universe as its temperature cooled.

- Isotope fractionation occurs during a phase transition, the ratio of light to heavy isotopes in the involved molecules changes. When water vapor condenses (an equilibrium fractionation), the heavier water isotopes (18O and 2H) become enriched in the liquid phase while the lighter isotopes (16O and 1H) tend toward the vapor phase.[1]

Phase transitions occur when the thermodynamic free energy of a system is non-analytic for some choice of thermodynamic variables (cf. phases). This condition generally stems from the interactions of a large number of particles in a system, and does not appear in systems that are too small.

At the phase transition point (for instance, boiling point) the two phases of a substance, liquid and vapor, have identical free energies and therefore are equally likely to exist. Below the boiling point, the liquid is the more stable state of the two, whereas above the gaseous form is preferred.

It is sometimes possible to change the state of a system diabatically (as opposed to adiabatically) in such a way that it can be brought past a phase transition point without undergoing a phase transition. The resulting state is metastable, i.e., less stable than the phase to which the transition would have occurred, but not unstable either. This occurs in superheating, supercooling, and supersaturation, for example.

Classifications

Ehrenfest classification

Paul Ehrenfest classified phase transitions based on the behavior of the thermodynamic free energy as a function of other thermodynamic variables. Under this scheme, phase transitions were labeled by the lowest derivative of the free energy that is discontinuous at the transition. First-order phase transitions exhibit a discontinuity in the first derivative of the free energy with respect to some thermodynamic variable.[2] The various solid/liquid/gas transitions are classified as first-order transitions because they involve a discontinuous change in density, which is the first derivative of the free energy with respect to chemical potential. Second-order phase transitions are continuous in the first derivative (the order parameter, which is the first derivative of the free energy with respect to the external field, is continuous across the transition) but exhibit discontinuity in a second derivative of the free energy.[2] These include the ferromagnetic phase transition in materials such as iron, where the magnetization, which is the first derivative of the free energy with respect to the applied magnetic field strength, increases continuously from zero as the temperature is lowered below the Curie temperature. The magnetic susceptibility, the second derivative of the free energy with the field, changes discontinuously. Under the Ehrenfest classification scheme, there could in principle be third, fourth, and higher-order phase transitions.

Though useful, Ehrenfests classification has been found to be an inaccurate method of classifying phase transitions, for it does not take into account the case where a derivative of free energy diverges (which is only possible in the thermodynamic limit). For instance, in the ferromagnetic transition, the heat capacity diverges to infinity.

Modern classifications

In the modern classification scheme, phase transitions are divided into two broad categories, named similarly to the Ehrenfest classes:

First-order phase transitions are those that involve a latent heat. During such a transition, a system either absorbs or releases a fixed (and typically large) amount of energy. During this process, the temperature of the system will stay constant as heat is added: the system is in a "mixed-phase regime" in which some parts of the system have completed the transition and others have not. Familiar examples are the melting of ice or the boiling of water (the water does not instantly turn into vapor, but forms a turbulent mixture of liquid water and vapor bubbles). Imry and Wortis showed that quenched disorder can broaden a first-order transition in that the transformation is completed over a finite range of temperatures, but phenomena like supercooling and superheating survive and hysteresis is observed on thermal cycling.[3][4][5]

Second-order phase transitions are also called continuous phase transitions. They are characterized by a divergent susceptibility, an infinite correlation length, and a power-law decay of correlations near criticality. Examples of second-order phase transitions are the ferromagnetic transition, superconducting transition (for a Type-I superconductor the phase transition is second-order at zero external field and for a Type-II superconductor the phase transition is second-order for both normal state-mixed state and mixed state-superconducting state transitions) and the superfluid transition. In contrast to viscosity, thermal expansion and heat capacity of amorphous materials show a relatively sudden change at the glass transition temperature [6] which enable quite exactly to detect it using differential scanning calorimetry measurements. Lev Landau gave a phenomenological theory of second order phase transitions.

Apart from isolated, simple phase transitions, there exist transition lines as well as multicritical points, when varying external parameters like the magnetic field, composition,...

Several transitions are known as the infinite-order phase transitions. They are continuous but break no symmetries. The most famous example is the Kosterlitz–Thouless transition in the two-dimensional XY model. Many quantum phase transitions, e.g., in two-dimensional electron gases, belong to this class.

The liquid-glass transition is observed in many polymers and other liquids that can be supercooled far below the melting point of the crystalline phase. This is atypical in several respects. It is not a transition between thermodynamic ground states: it is widely believed that the true ground state is always crystalline. Glass is a quenched disorder state, and its entropy, density, and so on, depend on the thermal history. Therefore, the glass transition is primarily a dynamic phenomenon: on cooling a liquid, internal degrees of freedom successively fall out of equilibrium. Some theoretical methods predict an underlying phase transition in the hypothetical limit of infinitely long relaxation times.[7][8] No direct experimental evidence supports the existence of these transitions.

Characteristic properties

Phase Coexistence

A disorder-broadened first order transition occurs over a finite range of temperatures with the fraction of the low-temperature equilibrium phase grows from zero to one (100%) as the temperature is lowered. This continuous variation of the coexisting fractions with temperature raised interesting possibilities. On cooling, some liquids vitrify into a glass rather than transform to the equilibrium crystal phase. This happens if the cooling rate is faster than a critical cooling rate, and is attributed to the molecular motions becoming so slow that the molecules cannot rearrange into the crystal positions.[9] This slowing down happens below a glass-formation temperature Tg, which may depend on the applied pressure.,[10][11] If the first-order freezing transition occurs over a range of temperatures, and Tg falls within this range, then there is an interesting possibility that the transition is arrested when it is partial and incomplete. Extending these ideas to first order magnetic transitions being arrested at low temperatures, resulted in the observation of incomplete magnetic transitions, with two magnetic phases coexisting, down to the lowest temperature. First reported in the case of a ferromagnetic to anti-ferromagnetic transition,[12] such persistent phase coexistence has now been reported across a variety of first order magnetic transitions. These include colossal-magnetoresistance manganite materials,[13][14] magnetocaloric materials,[15] magnetic shape memory materials,[16] and other materials.[17] The interesting feature of these observations of Tg falling within the temperature range over which the transition occurs is that the first order magnetic transition is influenced by magnetic field, just like the structural transition is influenced by pressure. The relative ease with which magnetic field can be controlled, in contrast to pressure, raises the possibility that one can study the interplay between Tg and Tc in an exhaustive way. Phase coexistence across first order magnetic transitions will then enable the resolution of outstanding issues in understanding glasses.

Critical points

In any system containing liquid and gaseous phases, there exists a special combination of pressure and temperature, known as the critical point, at which the transition between liquid and gas becomes a second-order transition. Near the critical point, the fluid is sufficiently hot and compressed that the distinction between the liquid and gaseous phases is almost non-existent. This is associated with the phenomenon of critical opalescence, a milky appearance of the liquid due to density fluctuations at all possible wavelengths (including those of visible light).

Symmetry

Order parameters

An order parameter is a measure of the degree of order across the boundaries in a phase transition system; it normally ranges between zero in one phase (usually above the critical point) and nonzero in the other.[18] At the critical point, the order parameter susceptibility will usually diverge.

An example of an order parameter is the net magnetization in a ferromagnetic system undergoing a phase transition. For liquid/gas transitions, the order parameter is the difference of the densities.

From a theoretical perspective, order parameters arise from symmetry breaking. When this happens, one needs to introduce one or more extra variables to describe the state of the system. For example, in the ferromagnetic phase, one must provide the net magnetization, whose direction was spontaneously chosen when the system cooled below the Curie point. However, note that order parameters can also be defined for non-symmetry-breaking transitions. Some phase transitions, such as superconducting and ferromagnetic, can have order parameters for more than one degree of freedom. In such phases, the order parameter may take the form of a complex number, a vector, or even a tensor, the magnitude of which goes to zero at the phase transition.

There also exist dual descriptions of phase transitions in terms of disorder parameters. These indicate the presence of line-like excitations such as vortex- or defect lines.

Relevance in cosmology

Symmetry-breaking phase transitions play an important role in cosmology. It has been speculated[according to whom?] that, in the hot early universe, the vacuum (i.e. the various quantum fields that fill space) possessed a large number of symmetries. As the universe expanded and cooled, the vacuum underwent a series of symmetry-breaking phase transitions. For example, the electroweak transition broke the SU(2)×U(1) symmetry of the electroweak field into the U(1) symmetry of the present-day electromagnetic field. This transition is important to understanding the asymmetry between the amount of matter and antimatter in the present-day universe (see electroweak baryogenesis.)

Progressive phase transitions in an expanding universe are implicated in the development of order in the universe, as is illustrated by the work of Eric Chaisson[19] and David Layzer.[20] See also Relational order theories.

Critical exponents and universality classes

Continuous phase transitions are easier to study than first-order transitions due to the absence of latent heat, and they have been discovered to have many interesting properties. The phenomena associated with continuous phase transitions are called critical phenomena, due to their association with critical points.

It turns out that continuous phase transitions can be characterized by parameters known as critical exponents. The most important one is perhaps the exponent describing the divergence of the thermal correlation length by approaching the transition. For instance, let us examine the behavior of the heat capacity near such a transition. We vary the temperature T of the system while keeping all the other thermodynamic variables fixed, and find that the transition occurs at some critical temperature Tc. When T is near Tc, the heat capacity C typically has a power law behavior:

Such a behaviour has the heat capacity of amorphous materials near the glass transition temperature where the universal critical exponent α = 0.59 [21] A similar behavior, but with the exponent  instead of

instead of  , applies for the correlation length.

, applies for the correlation length.

The exponent  is positive. This is different with

is positive. This is different with  . Its actual value depends on the type of phase transition we are considering.

. Its actual value depends on the type of phase transition we are considering.

For -1 < α < 0, the heat capacity has a "kink" at the transition temperature. This is the behavior of liquid helium at the lambda transition from a normal state to the superfluid state, for which experiments have found α = -0.013±0.003. At least one experiment was performed in the zero-gravity conditions of an orbiting satellite to minimize pressure differences in the sample.[22] This experimental value of α agrees with theoretical predictions based on variational perturbation theory.[23]

For 0 < α < 1, the heat capacity diverges at the transition temperature (though, since α < 1, the enthalpy stays finite). An example of such behavior is the 3-dimensional ferromagnetic phase transition. In the three-dimensional Ising model for uniaxial magnets, detailed theoretical studies have yielded the exponent α ∼ +0.110.

Some model systems do not obey a power-law behavior. For example, mean field theory predicts a finite discontinuity of the heat capacity at the transition temperature, and the two-dimensional Ising model has a logarithmic divergence. However, these systems are limiting cases and an exception to the rule. Real phase transitions exhibit power-law behavior.

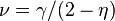

Several other critical exponents - β, γ, δ, ν, and η - are defined, examining the power law behavior of a measurable physical quantity near the phase transition. Exponents are related by scaling relations such as  ,

,  . It can be shown that there are only two independent exponents, e.g.

. It can be shown that there are only two independent exponents, e.g.  and

and  .

.

It is a remarkable fact that phase transitions arising in different systems often possess the same set of critical exponents. This phenomenon is known as universality. For example, the critical exponents at the liquid-gas critical point have been found to be independent of the chemical composition of the fluid. More amazingly, but understandable from above, they are an exact match for the critical exponents of the ferromagnetic phase transition in uniaxial magnets. Such systems are said to be in the same universality class. Universality is a prediction of the renormalization group theory of phase transitions, which states that the thermodynamic properties of a system near a phase transition depend only on a small number of features, such as dimensionality and symmetry, and are insensitive to the underlying microscopic properties of the system. Again, the divergency of the correlation length is the essential point.

Critical slowing down and other phenomena

There are also other critical phenomena; e.g., besides static functions there is also critical dynamics. As a consequence, at a phase transition one may observe critical slowing down or speeding up. The large static universality classes of a continuous phase transition split into smaller dynamic universality classes. In addition to the critical exponents, there are also universal relations for certain static or dynamic functions of the magnetic fields and temperature differences from the critical value.

Percolation theory

Another phenomenon which shows phase transitions and critical exponents is percolation. The simplest example is perhaps percolation in a two dimensional square lattice. Sites are randomly occupied with probability p. For small values of p the occupied sites form only small clusters. At a certain threshold pc a giant cluster is formed and we have a second order phase transition.[24] The behavior of P∞ near pc is, P∞~(p-pc)β, where β is a critical exponent.

Phase transitions in biological systems

Phase transitions play many important roles in biological systems. Examples include the lipid bilayer formation, the coil-globule transition in the process of protein folding and DNA melting, liquid crystal-like transitions in the process of DNA condensation, and cooperative ligand binding to DNA and proteins with the character of phase transition.[25]

In biolgical membranes, gel to liquid crystalline phase transitions play a very critical role in physiological functioning of biomembranes. In gel phase, due to low fluidity of membrane lipid fatty-acyl chains, membrane proteins have restricted movement and thus are restrained in exercise of their physilogical role. Plants depend critically on photosynthesis by chloroplast thylakoid membranes which are exposed cold environmental temperatures. Thylakoid membranes retain innate fluidity even at relatively low temperatures because of high degree of fatty-acyl disorder allowed by their high content of linolenic acid, 18-carbon chain with 3-double bonds.[26] Gel-to-liquid crystalline phase transition temperature of biological membranes can be measured many techniques including calorimetry, flouorescence, spin label electron paramagnetic resonance and NMR by recording measurements of the concerned parameter by at series of sample temperatures. A simple method for its determination from 13-C NMR line intensities has also been proposed.[27]

See also

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

| Phases · Phase transition |

- Allotropy

- Autocatalytic reactions and order creation

- Crystal growth

- Differential scanning calorimetry

- Diffusionless transformations

- Ehrenfest equations

- Jamming (physics)

- Kelvin probe force microscope

- Landau theory of second order phase transitions

- Laser-heated pedestal growth

- List of states of matter

- Micro-Pulling-Down

- Percolation theory

- Phase separation

- Superfluid film

- Superradiant phase transition

References

- Carol Kendall (2004). "Fundamentals of Stable Isotope Geochemistry". USGS. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

- Blundell, Stephen J.; Katherine M. Blundell (2008). Concepts in Thermal Physics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856770-7.

- Y. Imry and M. Wortis, Phys. Rev. B 19, 3580 (1979)

- K. Kumar et al, Phys. Rev. B 73, 184435 (2006)

- G. Pasquini et al, Phys. Rev. Lett 100, 247003 (2008).

- M.I. Ojovan. Ordering and structural changes at the glass-liquid transition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 382, 79-86 (2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2013.10.016

- Gotze, Wolfgang. "Complex Dynamics of Glass-Forming Liquids: A Mode-Coupling Theory."

- Lubchenko, V. Wolynes, P.G. "Theory of Structural Glasses and Supercooled Liquids" Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 2007, Vol 58. Pg 235.

- A.L.Greer, Science 267 (1995) 1947

- G. Tarjus, Nature Nature 448 (2007) 758

- M.I. Ojovan. Ordering and structural changes at the glass-liquid transition. J. Non-Cryst. Solids, 382, 79-86 (2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2013.10.016

- M.A.Manekar et al, Physical Review B 64 (2001) 104416

- A.Banerjee et al, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 18 (2006) L605

- W. Wu et al, Nature Materials 5 (2006) 881

- S.B.Roy et al, Physical Review B 74 (2006) 012403

- A.Lakhani et al, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 24 (2012) 386004

- P.Kushwaha et al, Physical Review B 80 (2009) 174413

- A. D. McNaught and A. Wilkinson (ed.). "Compendium of Chemical Terminology". IUPAC. ISBN 0-86542-684-8. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- Chaisson, Cosmic Evolution, Harvard, 2001

- David Layzer, Cosmogenesis, The Development of Order in the Universe, Oxford Univ. Press, 1991

- M.I. Ojovan, W.E. Lee. Topologically disordered systems at the glass transition. J. Phys.: Condensed Matter, 18, 11507-11520 (2006). http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1958/

- Lipa, J.; Nissen, J.; Stricker, D.; Swanson, D.; Chui, T. (2003). "Specific heat of liquid helium in zero gravity very near the lambda point". Physical Review B 68 (17). arXiv:cond-mat/0310163. Bibcode:2003PhRvB..68q4518L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.68.174518.

- Kleinert, Hagen (1999). "Critical exponents from seven-loop strong-coupling φ4 theory in three dimensions". Physical Review D 60 (8). arXiv:hep-th/9812197. Bibcode:1999PhRvD..60h5001K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.60.085001.

- Armin Bunde and Shlomo Havlin (1996). Fractals and Disordered Systems. Springer.

- D.Y. Lando and V.B. Teif (2000). "Long-range interactions between ligands bound to a DNA molecule give rise to adsorption with the character of phase transition of the first kind". J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 17 (5): 903–911. doi:10.1080/07391102.2000.10506578.

- YashRoy R.C. (1987) 13-C NMR studies of lipid fatty acyl chains of chloroplast membranes. Indian Journal of Biochemistry and Biophysics, vol. 24(6), pp. 177-178.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230822408_13-C_NMR_studies_of_lipid_fatty_acyl_chains_of_chloroplast_membranes?ev=prf_pub

- YashRoy R C (1990) Determination of membrane lipid phase transition temperature from 13-C NMR intensities. Journal of Biochemical and Biophysical Methods, vol. 20, pp. 353-356.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/20790042_Determination_of_membrane_lipid_phase_transition_temperature_from_13C-NMR_intensities?ev=prf_pub

Further reading

- Anderson, P.W., Basic Notions of Condensed Matter Physics, Perseus Publishing (1997).

- Fisher, M.E., "The renormalization group in the theory of critical behavior", Rev. Mod. Phys. 46, 597–616 (1974).

- Goldenfeld, N., Lectures on Phase Transitions and the Renormalization Group, Perseus Publishing (1992).

- Ivancevic, Vladimir G; Ivancevic, Tijana T (2008), Chaos, Phase Transitions, Topology Change and Path Integrals, Berlin: Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-79356-4, retrieved 14 March 2013 e-ISBN 978-3-540-79357-1

- Kogut,J. and Wilson,K, "The Renormalization Group and the epsilon-Expansion", Phys. Rep. 12 (1974), 75.

- Krieger, Martin H., Constitutions of matter : mathematically modelling the most everyday of physical phenomena, University of Chicago Press, 1996. Contains a detailed pedagogical discussion of Onsagers solution of the 2-D Ising Model.

- Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M., Statistical Physics Part 1, vol. 5 of Course of Theoretical Physics, Pergamon Press, 3rd Ed. (1994).

- Kleinert, H., Gauge Fields in Condensed Matter, Vol. I, "Superfluid and Vortex lines; Disorder Fields, Phase Transitions,", pp. 1–742, World Scientific (Singapore, 1989); Paperback ISBN 9971-5-0210-0 (readable online physik.fu-berlin.de)

- Kleinert, H. and Verena Schulte-Frohlinde, Critical Properties of φ4-Theories, World Scientific (Singapore, 2001); Paperback ISBN 981-02-4659-5 (readable online here).

- Mussardo G., "Statistical Field Theory. An Introduction to Exactly Solved Models of Statistical Physics", Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Schroeder, Manfred R., Fractals, chaos, power laws : minutes from an infinite paradise, New York: W. H. Freeman, 1991. Very well-written book in "semi-popular" style—not a textbook—aimed at an audience with some training in mathematics and the physical sciences. Explains what scaling in phase transitions is all about, among other things.

- Yeomans J. M., Statistical Mechanics of Phase Transitions, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- H. E. Stanley, Introduction to Phase Transitions and Critical Phenomena (Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York 1971).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Phase changes. |

- Interactive Phase Transitions on lattices with Java applets

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||